Table of Contents

Shareholder Wealth Maximization and Accounting Irregularities

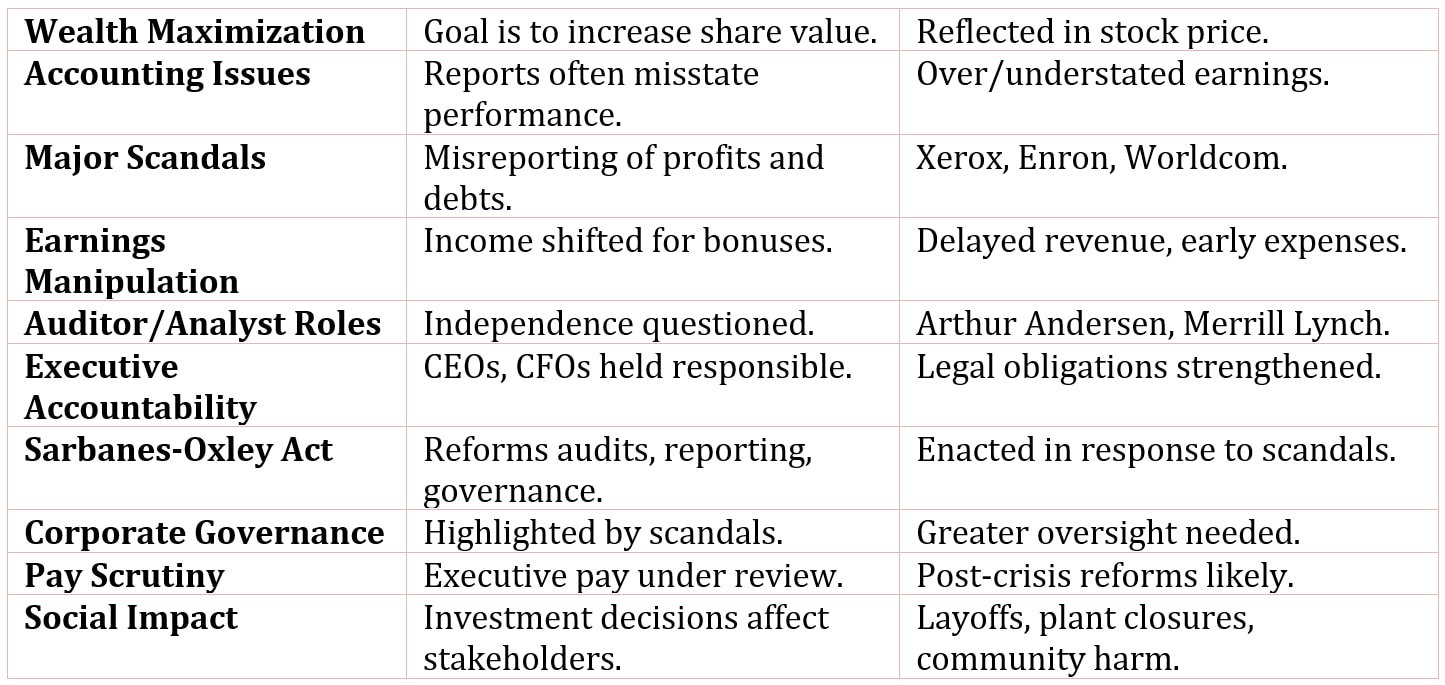

Shareholder wealth maximization refers to the corporate objective of increasing the value of the firm as reflected in the price of its shares, thereby maximizing returns to shareholders.

There have been a number of scandals and allegations regarding the financial information that is being reported to shareholders and the market.

Financial results reported in the income statements and balance sheets of some companies indicated much better performance than the true performance or much better financial condition than actual. Examples include Xerox, which was forced to restate earnings for several years because it had inflated pretax profits by $1.4 billion, Enron, which was accused of inflating earnings and hiding substantial debt, and Worldcom, which failed to properly account for $3.8 billion of expenses.

However, some companies have also encountered problems when managers understate earnings. For example, if a company’s earnings are not sufficient to meet bonus targets, by understating income in one period-for example, moving expenses forward in time or delaying recognition of revenues-there is a better possibility that the company will meet the bonus targets in the following year.

Along with these financial reporting issues, the independence of the auditors and the role of financial analysts have been brought to the forefront. For example, the now-defunct public accounting company of Arthur Andersen was found guilty of obstruction of justice in 2002 for their role in the shredding of documents relating to Enron. As an example of the problems associated with financial analysts, the securities company of Merrill Lynch paid a $100 million fine for their role in hyping stocks to help win investment-banking business.

It is unclear at this time the extent to which these scandals and problems were the result of simply bad decisions or due to corruption. The eagerness of managers to present favorable results to shareholders and the market appears to be a factor in several instances. And personal enrichment at the expense of shareholders seems to explain some cases. Whatever the motivation, chief executive officers (CEOs), chief financial officers (CFOs), and board members are being held directly accountable for financial disclosures.

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act, passed in 2002, addresses these and other issues pertaining to disclosures and governance in public corporations. This Act addresses audits by independent public accountants, financial reporting and disclosures, conflicts of interest, and corporate governance at public companies. Each of the provisions of this Act can be traced to one or more scandals that occurred in the few years leading up to the passage of the Act.

The accounting scandals created an awareness of the importance of corporate governance, the importance of the independence of the public accounting auditing function, the role of financial analysts, and the responsibilities of CEOs and CFOs.

The recent economic crisis has again raised the issue of pay-for-performance as companies receiving government bailouts are scrutinized for their executive pay practices. This suggests that more reform may be necessary to insure transparency of financial information and a better linkage between pay and performance.

Shareholder Wealth Maximization and Social Responsibility

When financial managers assess a potential investment in a new product, they examine the risks and the potential benefits and costs. If the risk-adjusted benefits do not outweigh the costs, they will not invest. Similarly, managers assess current investments for the same purpose; if benefits do not continue to outweigh costs, they will not continue to invest in the product but will shift their investment elsewhere. This is consistent with the goal of shareholder wealth maximization and with the efficient allocation of resources in the economy.

Discontinuing investment in an unprofitable business, however, may mean effects on other stakeholders of the company: closing down plants, laying off workers, affecting supplier’s businesses, and, perhaps destroying an entire town that depends on the business for income. So decisions to invest or disinvest may affect great numbers of people.