Table of Contents

The Agency Relationship

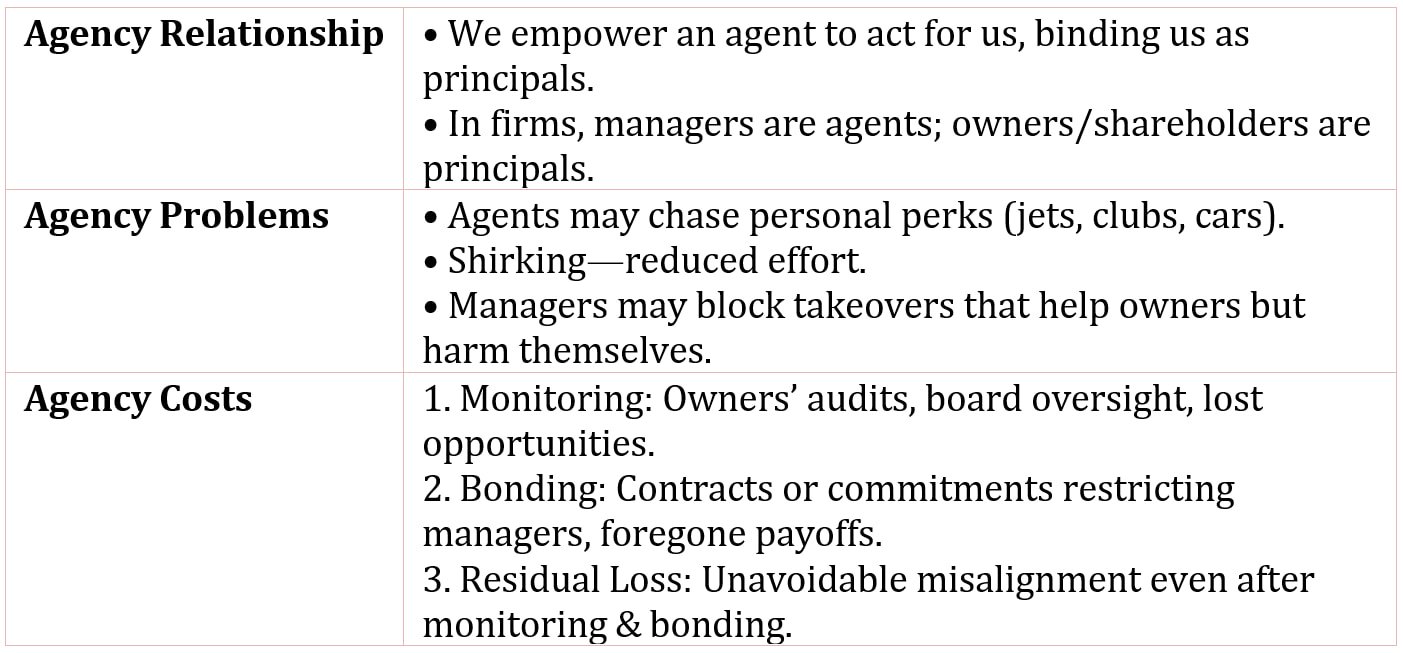

An agency relationship is a fiduciary connection in which one party, called the principal, authorizes another party, the agent, to act on their behalf in business or legal matters. This relationship is foundational in corporate governance, where shareholders (principals) entrust managers (agents) to operate the company and make decisions in their best interest.

An agency relationship exists when we authorize another to act for us, so that their authorized acts legally bind us as if performed by us personally.

If you are the sole owner of a business, you make the decisions that affect your own well-being. But what if you are a financial manager of a business and you are not the sole owner? In this case, you are making decisions for owners other than yourself; you, the financial manager, are an agent.

An agent is a person who acts for-and exerts powers of-another person or group of persons. The person (or group of persons) the agent represents is referred to as the principal. The relationship between the agent and his or her principal is an agency relationship. There is an agency relationship between the managers and the shareholders of corporations.

Problems with the Agency Relationship

In an agency relationship, the agent is charged with the responsibility of acting for the principal. Is it possible the agent may not act in the best interest of the principal, but

instead act in his or her own self-interest? Yes-because the agent has his or her own objective of maximizing personal wealth.

In a large corporation, for example, the managers may enjoy many fringe benefits, such as golf club memberships, access to private jets, and company cars. These benefits (also called perquisites or perks) may be useful in conducting business and may help attract or retain management personnel, but there is room for abuse. What if the managers start spending more time at the golf course than at their desks? What if they use the company jets for personal travel? What if they buy company cars for their teenagers to drive?

The abuse of perquisites imposes costs on the company-and ultimately on the owners of the company. There is also a possibility that managers who feel secure in their positions may not bother to expend their best efforts toward the business. This is referred to as shirking, and it too imposes a cost to the company.

Finally, there is the possibility that managers will act in their own selfinterest, rather than in the interest of the shareholders when those interests clash.

Defensiveness by corporate managers in the case of takeovers, whether warranted or not, emphasizes the potential for conflict between the interests of the owners and the interests of management.

Defending against a takeover that would not produce a benefit for the shareholders is consistent with management’s obligations. However, defending against a takeover that would produce a benefit for shareholders, but also a detriment to management (e.g., lost jobs), would be contrary to management’s duty to shareholders.

Costs of the Agency Relationship

There are costs involved with any effort to minimize the potential for conflict between the principal’s interest and the agent’s interest.

Such costs are called agency costs, and they are of three types:

- Monitoring costs

- Bonding costs

- Residual loss

1. Monitoring Costs

Monitoring costs are costs incurred by the principal to monitor or limit the actions of the agent. In a corporation, shareholders may require managers to periodically report on their activities via audited accounting statements, which are sent to shareholders.

The fees for auditing and preparing the financial statements and the management time lost in preparing such statements are monitoring costs. Another example is the implicit cost incurred when shareholders limit the decision-making power of managers. By doing so, the owners may miss profitable investment opportunities; the foregone profit is a monitoring cost.

The board of directors of a corporation has a fiduciary duty to shareholders; that is the legal responsibility to make decisions (or to see that decisions are made) that are in the best interests of shareholders. Part of that responsibility is to ensure that managerial decisions are also in the best interests of the shareholders. Therefore, at least part of the cost of having directors is a monitoring cost.

2. Bonding Costs

Bonding costs are incurred by agents to assure principals that they will act in the principal’s best interest. The name comes from the agent’s promise or bond to take certain actions. A manager may enter into a contract that requires him or her to stay on with the company even though another company acquires it; an implicit cost is then incurred by the manager, who foregoes other employment opportunities.

3. Residual Loss

When monitoring and bonding devices are used, there may be some divergence between the interests of principals and those of agents. The resulting cost, called the residual loss, is the implicit cost that results because the principal’s and the agent’s interests cannot be perfectly aligned even when monitoring and bonding costs are incurred.