Table of Contents

Dividend Policy in Finance

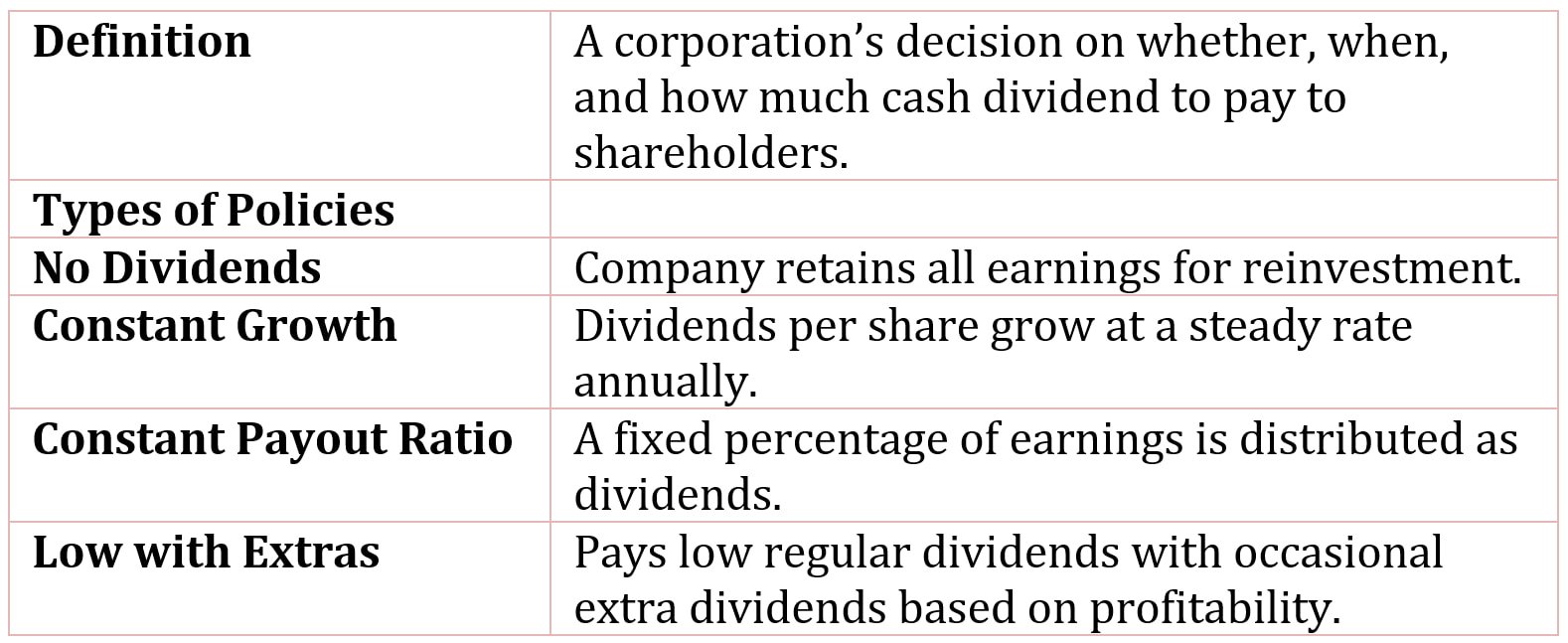

Dividend policy refers to a corporation’s strategic decision regarding whether, when, and how much cash dividend should be paid to shareholders.

There are several basic ways of describing acorporation’s dividend policy:

- No dividends.

- Constant growth in dividends per share.

- Constant payout ratio.

- Low regular dividends with periodic extra dividends.

The corporations that typically do not pay dividends are those that are generally viewed as younger, faster growing companies. For example, Microsoft Corporation was founded in 1975 and went public in 1986, but it did not pay a cash dividend until January 2003.

A common pattern of cash dividends tends to be the constant growth of dividends per share. Another pattern is the constant payout ratio. Many other companies in the food processing industry, such as Kellogg and Tootsie Roll Industries, pay dividends that are a relatively constant percentage of earnings.

Some companies display both a constant dividend payout ratio and a constant growth in dividends. This type of dividend pattern is characteristic of large, mature companies that have predictable earnings growth-the dividends growth tends to mimic the earnings growth, resulting in a constant payout.

U.S. corporations that pay dividends tend to pay either constant or increasing dividends per share. Dividends tend to be lower in industries that have many profitable opportunities to invest their earnings. But as a company matures and finds fewer and fewer profitable investment opportunities, it generally pays out a greater portion of its earnings in dividends.

Many corporations are reluctant to cut dividends because the corporation’s share price usually falls when a dividend reduction is announced. For example, the U.S. auto manufacturers cut dividends during the recession in the early 1990s.

As earnings per share declined the automakers did not cut dividends until earnings per share were negative-and in the case of General Motors, not until it had experienced two consecutive loss years. But as earnings recovered in the mid-1990s, dividends were increased.

Because investors tend to penalize companies that cut dividends, corporations tend to only raise their regular quarterly dividend when they are sure they can keep it up in the future. By giving a special or extra dividend, the corporation is able to provide more cash to the shareholders without committing itself to paying an increased dividend each period into the future.

There is no general agreement whether dividends should or should not be paid. Here are several views:

- The dividend irrelevance theory: The payment of dividends does not affect the value of the company since the investment decision is independent of the financing decision.

- The “bird in the hand” theory: Investors prefer a certain dividend stream to an uncertain price appreciation.

- The tax-preference explanation: Due to the way in which dividends are taxed, investors should prefer the retention of funds to the payment of dividends.

- The signaling explanation: Dividends provide a way for the management to inform investors about the company’s future prospects.

- The agency explanation: The payment of dividends forces the company to seek more external financing, which subjects the company to the scrutiny of investors.

The Dividend Irrelevance Theory

The dividend irrelevance argument was developed by Merton Miller and Franco Modigliani.

Basically, the argument is that if there is a perfect capital market-no taxes, no transactions costs, no costs related to issuing new securities, and no costs of sending or receiving information-the value of the corporation is unaffected by payment of dividends.

How can this be? Suppose investment decisions are fixed-that is, the company will invest in certain projects regardless how they are financed. The value of the corporation is the present value of all future cash flows of the company-which depend on the investment decisions that management makes, not on how these investments are financed.

If the investment decision is fixed, whether a corporation pays a dividend or not does not affect the value of the corporation.

A corporation raises additional funds either through earnings or by selling securities-sufficient to meet its investment decisions and its dividend decision. The dividend decision therefore affects only the financing decision-how much capital the company has to raise to fulfill its investment decisions.

The Miller and Modigliani argument implies that the dividend decision is a residual decision: If the company has no profitable investments to undertake, the company can pay out funds that would have gone to investments to shareholders. And whether or not the company pays dividends is of no consequence to the value of the company. In other words, dividends are irrelevant.

The “Bird in the Hand” Theory

A popular view is that dividends represent a sure thing relative to share price appreciation. The return to shareholders is comprised of two parts: the return from dividends-the dividend yield-and the return from the change in the share price-the capital yield.

Corporations generate earnings and can either pay them out in cash dividends or reinvest earnings in profitable investments, increasing the value of the stock and, hence, share price.

Once a dividend is paid, it is a certain cash flow. Shareholders can cash their quarterly dividend checks and reinvest the funds. But an increase in share price is not a sure thing. It only becomes a sure thing when the share’s price increases over the price the shareholder paid and he or she sells the shares.

The Tax-Preference Explanation

If dividend income is taxed at the same rates as capital gain income, investors may prefer capital gains because of the time value of money: capital gains are only taxed when realized-that is, when the investor sells the stock-whereas dividend income is taxed when received.

If, on the other hand, dividend income is taxed at rates higher than that applied to capital gain income, investors should prefer stock price appreciation to dividend income because of both the time value of money and the lower rates.

Historically, capital gain income in the United States has been taxed at rates lower than that applied to dividend income for individual investors. However, the current situation for individuals is that dividend income and capital gain income are taxed at the same rates.

Even with the same rates applied to income, capital gain income is still preferred because the tax on any stock appreciation is deferred until the stock is sold-which can be many years into the future.

The Signaling Explanation

Companies that pay dividends seem to maintain a relatively stable dividend, either in terms of a constant or growing dividend payout ratio or in terms of a constant or growing dividend per share. And when companies change their dividend-either increasing or reducing (“cutting”) the dividend-the price of the company’s shares seems to be affected: When a dividend is increased, the price of the company’s shares typically goes up; when a dividend is cut, the price usually goes down. This reaction is attributed to investors’ perception of the meaning of the dividend change: Increases are good news, decreases are bad news.

The board of directors is likely to have some information that investors do not have, a change in dividend may be a way for the board to signal this private information.

Because most boards of directors are aware that when dividends are lowered, the price of a share usually falls, most investors do not expect boards to increase a dividend unless they thought the company could maintain it into the future. Realizing this, investors may view a dividend increase as the board’s increased confidence in the future operating performance of the company.

The Agency Explanation

The relation between the owners and the managers of a company is an agency relationship: The owners are the principals and the managers are the agents. Management is charged with acting in the best interests of the owners. Nevertheless, there are possibilities for conflicts between the interests of the two.

If the company pays a dividend, the company may be forced to raise new capital outside of the company-that is, issue new securities instead of using internally generated capital-subjecting them to the scrutiny of equity research analysts and other investors. This extra scrutiny helps reduce the possibility that managers will not work in the best interests of the shareholders. But issuing new securities is not costless.

There are costs of issuing new securities-flotation costs. In “agency theory-speak,” these costs are part of monitoring costs-incurred to help monitor the managers’ behavior and insure behavior is consistent with shareholder wealth maximization.

The payment of dividends also reduces the amount of free cash flow under control of management. Free cash flow is the cash in excess of the cash needed to finance profitable investment opportunities.

A profitable investment opportunity is any investment that provides the company with a return greater than what shareholders could get elsewhere on their money-that is, a return greater than the shareholders’ opportunity cost.

Because free cash flow is the cash flow left over after all profitable projects are undertaken, the only projects left are the unprofitable ones. Should free cash be reinvested in the unprofitable investments or paid out to shareholders? Of course if boards make decisions consistent with shareholder wealth maximization, any free cash flow should be paid out to shareholders since-by the definition of a profitable investment opportunity-the shareholders could get a better return investing the funds they receive.