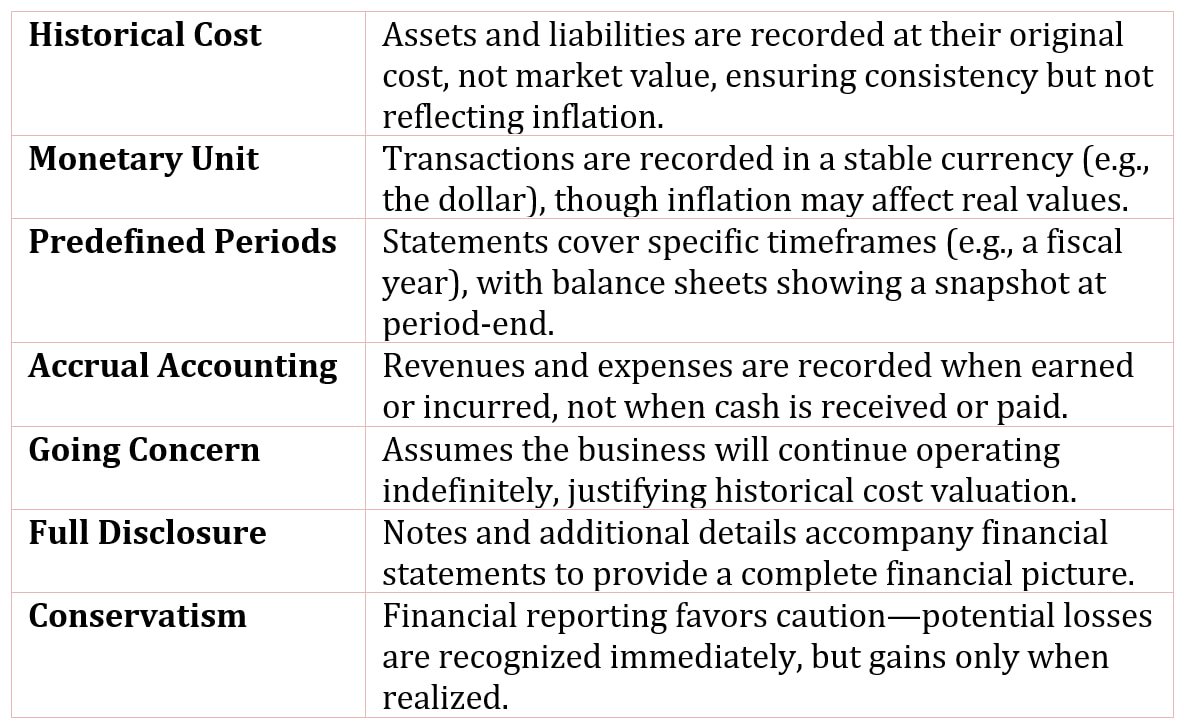

Table of Contents

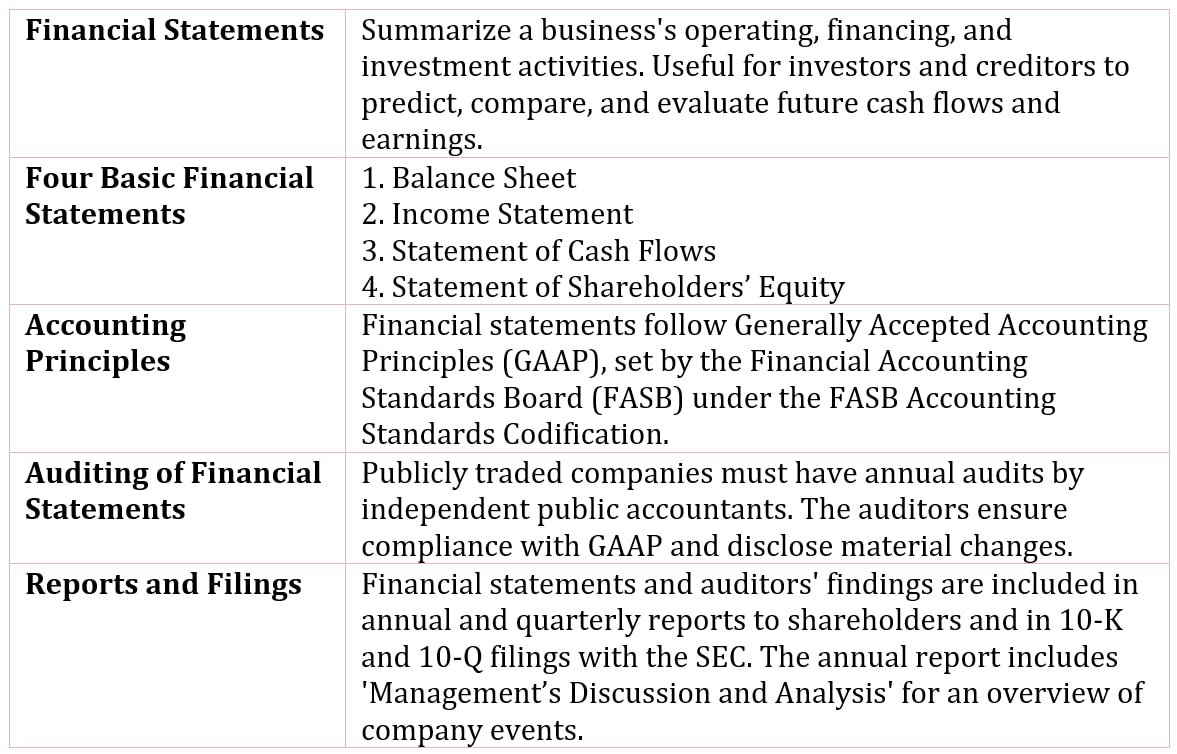

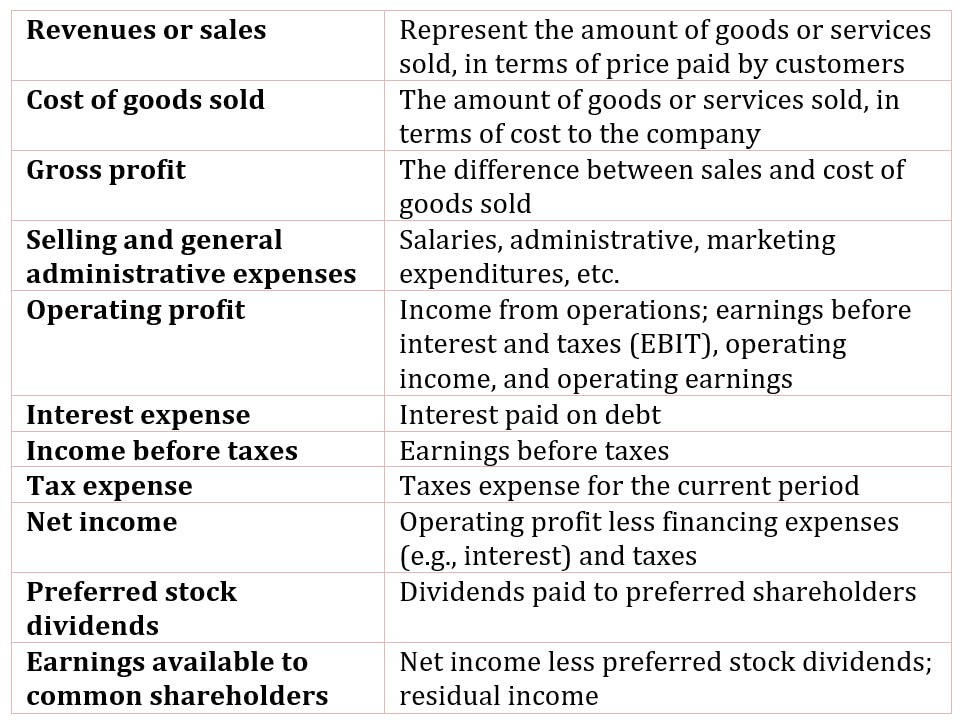

The Income Statement

The income statement is a summary of operating performance over a period of time (e.g., a fiscal quarter or a fiscal year).

We start with the revenue of the company over a period of time and then subtract the costs and expenses related to that revenue. The bottom line of the income statement consists of the owners’ earnings for the period.

The cost of sales, also referred to as the cost of goods sold, is deducted from revenues, producing a gross profit; that is, a profit without considering all other general operating costs.

These general operating expenses are those expenses related to the support of the general operations of the company, which includes salaries, marketing costs, and research and development.

Depreciation, which is the amortized cost of physical assets, is also deducted from gross profit. The amount of the depreciation expense represents the cost of the wear and tear on the property, plant, and equipment of the company.

Once we have the operating income, we have summarized the company’s performance with respect to the operations of the business. But there is generally more to the company’s performance.

From operating income, we deduct interest expense and add any interest income. Further, adjustments are made for any other income or cost that is not a part of the company’s core business.

Earnings Per Share

Companies provide information on earnings per share (EPS) in their annual and quarterly financial statement information, as well as in their periodic press releases. Generally, EPS is calculated as net income divided by the number of shares outstanding. Companies must report both basic and diluted earnings per share.

Basic earnings per share is net income (minus preferred dividends) divided by the average number of shares outstanding. Diluted earnings per share is net income (minus preferred dividends) divided by the number of shares outstanding considering all dilutive securities (e.g., convertible debt, options).

Diluted earnings per share, therefore, gives the shareholder information about the potential dilution of earnings. For companies with a large number of dilutive securities (e.g., stock options, convertible preferred stock, or convertible bonds), there can be a significant difference between basic and diluted EPS.

More on Depreciation

There are different methods that can be used to allocate an asset’s cost over its life. Generally, if the asset is expected to have value at the end of its economic life, the expected value, referred to as a salvage value (or residual value), is not depreciated; rather, the asset is depreciated down to its salvage value.

There are different methods of depreciation that we classify as either straight-line or accelerated.

- Straight-line depreciation allocates the cost (less salvage value) in a uniform manner (equal amount per period) throughout the asset’s life.

- Accelerated depreciation allocates the asset’s cost (less salvage value) such that more depreciation is taken in the earlier years of the asset’s life.

There are alternative accelerated methods available, including:

- Declining balance method, in which a constant rate applied to a declining amount (the undepreciated cost).

- Sum-of-the-year’s digits method, in which a declining rate applied to the asset’s depreciable basis and this rate is ratio of the remaining years divided by the sum of the years.

Accelerated methods result in higher depreciation expenses in earlier years, relative to straight-line. As a result, accelerated methods result in lower reported earnings in earlier years, relative to straight-line, but also lower net property, plant, and equipment in earlier years as well.

Comparing companies, it is important to understand whether the companies use different methods of depreciation because the choice of depreciation method affects both the balance sheet (through the carrying value of the asset) and the income statement (through the depreciation expense).

A major source of deferred income tax liability and deferred tax assets is the accounting method used for financial reporting purposes and tax purposes.

In the case of financial accounting purposes, the company chooses the method that best reflects how its assets lose value over time, though most companies use the straight-line method. However, for tax purposes the company has no choice but to use the prescribed rates of depreciation, using the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS).

For tax purposes, a company does not have discretion over the asset’s depreciable life or the rate of depreciation-they must use the MACRS system.